Nick Pelios

Freediver, Creator

Nick Pelios

Freediver, Creator

Nick Pelios

Freediver, Creator

Nick Pelios

Freediver, Creator

Freediving is often described as a sport of relaxation. That idea sounds simple. Relax and you will dive further. In practice, relaxation is a skill that many divers struggle to achieve, especially as the target depth increases. Muscle tension is one of the most common obstacles that limit performance in the constant weight disciplines. Even experienced divers who train regularly can find themselves stuck at a depth because their body is doing far more work than required.

Understanding how tension harms performance and learning how to reduce it can unlock significant improvements without needing to increase strength or technical capability.

Muscles use oxygen when they contract. That is the most direct way tension harms deep diving. A freediver already has a limited supply of oxygen and a rising level of carbon dioxide each second underwater. Any unnecessary contraction uses up this fuel. The body then starts sending stronger breathing signals sooner. The urge to breathe increases. The perceived difficulty of the dive increases. The dive ends earlier.

There is also a direct impact on equalization. Tension in the neck, shoulders, tongue, and jaw can restrict Eustachian tube function, which means that equalization becomes more effortful. A diver might burn energy simply trying to get air to the right place, and the more they struggle, the more stress increases. Many divers think they have an equalization skills issue when in reality they have a tension issue.

Another hidden cost of tension is related to hydrodynamics. Water is dense. Every shape that moves through it experiences drag. When a diver is stiff, the body becomes less streamlined. The spine might bend awkwardly. Fins might not track correctly behind the hips. Fin strokes become less efficient. The diver then needs more strokes to travel the same distance. More strokes mean more muscular contraction and more wasted energy.

The body also communicates tension to the mind. A tight body sends a message that something is not right. The brain interprets this feedback as a sign of effort or danger. Anxiety rises. Heart rate rises. The dive reflex does not engage as strongly. The very mechanism that keeps divers safe and efficient underwater is delayed or reduced.

Tension is therefore expensive. It spends oxygen, creates drag, sabotages equalization, and increases stress. For freedivers chasing deeper dives, every unnecessary muscle contraction is an obstacle to success.

Many divers first experience tension before they even get into the water. Anticipation and performance pressure can lead to subconscious tightening. Shoulders lift. Breathing becomes less natural. The diaphragm might become rigid rather than moving freely. Even the face can tighten. These small changes have a cumulative effect that surfaces later in the dive.

Once a diver starts descending, there are predictable moments when tension usually increases. The first is the transition from the surface to negative buoyancy. At the top of the dive the diver must generate propulsion, maintain body position, and perform regular equalization. The body is working and the mind is adjusting to pressure. This can create stress, even if low level.

Another trigger appears when the diver hits the point of neutral buoyancy and begins to sink. The body is now surrendering control to gravity. For some divers, letting go of active control produces anxiety. The instinct is to tense up and resist the fall. The more a diver tries to control the freefall, the more oxygen is wasted.

Deeper in the dive, the final source of tension comes from rising levels of carbon dioxide. High CO2 makes the body want to breathe, and the brain often responds by engaging more muscles, as if bracing for discomfort. This tension reduces equalization efficiency and increases the descent effort exactly when relaxation is needed the most.

If any of these triggers are present, a diver may complete the dive, but the experience will feel harder than necessary. Progress slows. The plateau arrives. The diver looks for a new training method or a different piece of equipment, unaware that the root of the problem is in the body’s response to pressure and depth.

The first step to solving a tension problem is awareness. You cannot fix what you cannot feel. Divers often become so used to their discomfort that they consider it normal. A coach or dive buddy observing from the surface may notice stiffness that the diver does not feel. Body scanning is a useful approach. It involves paying attention to each section of the body before, during, and after a dive.

Common areas where unnecessary tension hides include the neck, shoulders, hands, glutes, and quadriceps. The jaw often holds tension that interrupts equalization. The arms grip the line too forcefully during the early part of the descent. Even the tongue can be tense. These muscles do not need to work during a well executed freefall.

Video analysis is valuable for identifying inefficient movement patterns. A diver who kicks from the knees rather than from the hips often carries tension in the quadriceps. A diver whose fins flare outward might be tightening the glutes. A diver whose torso bends may be contracting the abdominals too aggressively.

Many divers discover that their tension is connected to mental states rather than movement errors. If heart rate rises at the moment of freefall, the mind is probably resisting the sensation of surrendering to depth. If equalization becomes frantic at depth, stress may be triggering the jaw and tongue to tense.

Awareness removes guesswork. Once the specific sources of tension are known, training can target them directly.

Relaxation is not a passive state. It is trained through repetition and conscious control. Dry training can play a large role in teaching the body to stay calm under load.

Stretching improves mobility and reduces the likelihood of instinctive muscle guarding. Loose hips create a more efficient fin stroke. A flexible thoracic spine supports better body alignment. Relaxed shoulders allow a smoother arm position in the freefall. Stretching the tongue and jaw may feel unusual, but it directly supports better equalization at depth.

Strength training, when used correctly, also reduces tension. Strong muscles require less activation to produce the same movement. As a result, divers expend less oxygen. The goal is not maximum strength but optimal strength that supports long and controlled movement patterns.

Breathwork is another important foundation. Diaphragmatic breathing helps reduce tension in the chest and upper shoulders. Divers who rely heavily on accessory breathing muscles often carry unnecessary tightness in the upper body. Breath training should also build familiarity with elevated CO2 so that contractions and urge to breathe do not create anxiety that leads to muscle tightening.

Static breath holds train the mind to remain calm when breathing is restricted. The goal is not to fight contractions but to maintain a relaxed state so that the urge to breathe does not lead to high tension responses.

Finally, visualization can prepare the nervous system. The mind can rehearse a neutral buoyancy transition or a freefall scenario. Visualizing a controlled and relaxed response to pressure changes helps reduce real world anxiety.

The combination of stretching, strength, breathwork, and visualization builds a body and mind ready to relax efficiently underwater.

Technical refinement plays a key role in reducing muscle activation. Perfecting the first 20 meters is especially important for consistent performance.

A streamlined body uses less energy. Keeping the head neutral with the gaze downward reduces drag and removes neck strain. The arms should be passive and aligned to minimize water resistance and allow the spine to stay neutral.

Finning should come from the hips rather than the knees. Minimal knee bend prevents the quadriceps from overworking. The motion should be smooth and symmetrical. The tempo can slow as the body becomes less buoyant. Many divers kick too aggressively near the surface, burning energy unnecessarily.

Equalization technique must not rely on tension in the jaw or facial muscles. Divers who crunch their face to equalize are often wasting energy. Tongue placement and soft palate control should be trained to operate with minimal movement.

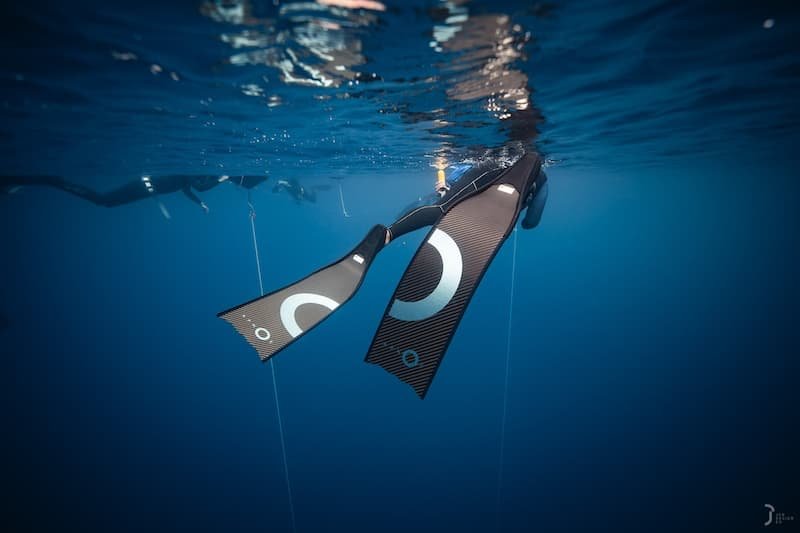

During freefall, the goal is to do nothing beyond required equalization. Hands and feet remain relaxed. Legs stay straight without actively holding them together. The diver trusts the fall. If the body begins to tense, the diver should consciously release the area. With practice, that release becomes automatic.

Technical relaxation is a skill. Each dive reinforces it. With enough repetitions, efficiency replaces effort.

Muscle tension is almost always linked to psychological tension. The brain’s main job is to protect the body. When it senses risk, it signals muscles to engage. In freediving, this instinct is usually counterproductive.

Understanding CO2 physiology helps the brain respond more calmly. Rising CO2 is not an emergency but a natural part of the dive reflex. High CO2 triggers stronger bradycardia and better blood redistribution. The uncomfortable urge to breathe does not mean that oxygen is gone. The body is still operating within a safe range if the dive plan and depth are appropriate for the diver’s skill level.

Mental rehearsal helps reframe high CO2 moments as expected and manageable. Before a dive, a diver can review the plan, visualize equalization landmarks, and set clear intentions for relaxation cues. A diver who accepts contractions rather than fighting them will be far more relaxed than one who reacts with fear.

Stress management continues after the dive. Reflecting on each repetition helps identify which moments triggered tension. Small improvements in response accumulate into noticeable performance gains.

When a diver releases unnecessary tension, several important improvements occur at once.

Oxygen consumption decreases. The dive reflex becomes stronger earlier in the dive. Hydrodynamics improve and propulsion becomes more efficient. Equalization requires less effort. The mind remains clearer, so decisions are better. Every aspect of the dive is made easier.

Relaxation also builds confidence. A deep dive that feels hard can damage motivation. A dive that feels smooth, even if not as deep yet, encourages further training. Reduced tension also lowers injury risk. A relaxed diver is less likely to strain soft tissue during strong kicks or stretching equalization maneuvers.

The path to deeper dives becomes predictable. Depth is no longer about pushing through discomfort. It becomes the natural result of improved efficiency.

Knowing that relaxation matters does not automatically change a dive. Habits must be built through structured practice.

Small goals are useful. A diver can focus on one relaxation objective per session. For example, releasing shoulders during the descent or maintaining a softer jaw during equalization. Once that goal is achieved consistently, the diver can move to another area.

Coaches and experienced buddies are important. They offer observations the diver cannot feel and can suggest adjustments before mistakes become ingrained habits.

Finally, patience is required. Relaxation is not a switch. It is learned slowly, but the improvements last much longer than a temporary increase in strength or fitness.