Olivia Møller

Freediver - Activist - Explorer

Olivia Møller

Freediver - Activist - Explorer

Olivia Møller

Freediver - Activist - Explorer

Olivia Møller

Freediver - Activist - Explorer

The ocean has always been a world shaped by gradients. Temperature, light, pressure, chemistry, and sound shift layer by layer, from the sun lit surface to the unbroken dark of the abyss. For millennia marine species have used these gradients as invisible architecture, carving out their niches within a constantly changing column of water. Climate change has disrupted this arrangement. As surface waters warm, currents shift, acidity increases, and ecosystems lose their familiar patterns, many species are beginning to move. Some migrate toward the poles. Others shift their breeding seasons or alter their diets. And in many parts of the world, an increasing number are abandoning the surface entirely, slipping deeper into the ocean in search of colder and more stable refuges. This vertical escape is subtle, often unnoticed by the casual eye, yet it reveals something profound about how the ocean functions and how marine life is adapting to a crisis unfolding faster than many organisms can manage.

For a freediver, the idea of finding refuge in depth is familiar on a personal level. The deeper you go, the more the world changes. Light dissolves into blue. Sound sharpens. The mind becomes quieter. Temperature gradients feel like thresholds between ecosystems. Descending along a line, you can sense that each layer holds its own community, its own rhythms, its own logic. But for marine species, these layers are not recreational spaces. They are survival zones. When the upper ocean warms, the warm layer thickens and becomes hostile to creatures shaped by cooler conditions. Their solution is movement. Downward movement. The change might only be a few meters at first, but as temperature profiles rise globally, the shifts become more pronounced. What freedivers experience as a thermocline is, for many organisms, a boundary that separates habitability from crisis.

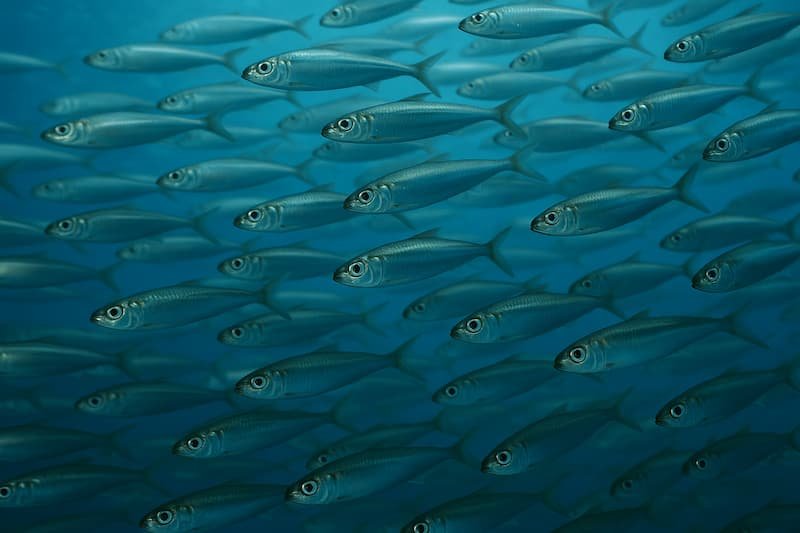

The most obvious reason for these downward migrations is temperature. Marine species are finely tuned to narrow thermal ranges. Even a few degrees of additional heat can alter metabolism, oxygen demand, growth rates, and reproductive timing. As surface waters warm faster than deeper layers, the vertical gradient becomes a potential lifeline. For example, sardines in the Mediterranean have been observed shifting their distributions deeper during heatwaves. They do not abandon the surface entirely, but their primary foraging and schooling depths change with seasonal warming. Similar patterns have been documented for mackerel, anchovies, and other pelagic fish, which historically moved horizontally but now adjust their behavior vertically as well.

Corals, which cannot migrate, suffer the most near the surface. As bleaching events increase, the shallow reefs that once thrived become barren. Yet in some regions deeper reefs remain resilient. These are known as mesophotic reefs, found between roughly thirty and one hundred meters. Light is reduced but still present, temperatures are more stable, and many coral species adapted to this zone are less susceptible to bleaching. These reefs may not replace shallow ecosystems, but they offer a sanctuary for associated fish and invertebrates, acting as reservoirs of biodiversity that could someday help replenish damaged areas. Their value becomes even more significant as shallow ecosystems continue to warm beyond survivable thresholds.

Some species shift deeper not only for temperature but also for oxygen. Warming reduces oxygen solubility in surface waters, creating expanding zones of low oxygen where few animals can survive. These zones often form between fifty and two hundred meters, depending on the region, but their depth and extent are changing. Species that once inhabited this middle zone now face a difficult choice. Move up to the hotter surface layer or move down toward colder waters where oxygen is more plentiful. Many choose the latter. This creates cascading changes in predator prey relationships. A deepening prey species forces its predators to adjust, and sometimes predators cannot follow. In the eastern Pacific, Humboldt squid have expanded their range vertically and geographically in response to temperature and oxygen changes, displacing other predators and altering entire food webs as they move.

For freedivers, these shifting distributions are sometimes visible during training or recreational dives. You might notice that a species once common at twenty meters now appears around thirty five. Seasonal changes make this even more obvious. A thermocline that used to sit predictably at twenty five meters might now drift deeper during heatwaves. Fish follow the cooler band. Large pelagics like amberjack, tuna, and wahoo may avoid the upper layer altogether during mid summer heat, hunting instead in the transitional depths where cold and warm water mix. From the perspective of a diver, it can feel like the fish have disappeared. In reality, they have simply moved to where their physiology allows them to function.

Depth also offers refuge from acidification. As the surface absorbs more carbon dioxide, acidity rises and interferes with the ability of certain species to build shells, regulate ions, or maintain internal balance. While acidification eventually mixes downward, the process is slow. Deeper water changes more gradually, providing a temporary buffer. Species like pteropods, tiny shelled organisms that form a major part of the ocean’s food chain, have been found retreating to deeper layers in regions where surface acidity has increased sharply. Their downward movement affects everything from salmon feeding grounds to the abundance of zooplankton eaten by larger predators.

Temperature, oxygen, and acidity are the main drivers, but depth also changes light and predation risk. In many warming regions, predators that favor cooler conditions dive deeper to hunt. This reshapes the structure of vertical communities. Some prey species dive even further down to escape, setting off a chain reaction through the water column. The movement is not random. It is a layered negotiation, a constant adjustment in search of balance. And with each adjustment, ecosystems are subtly rewritten.

The consequence of these shifts is not simple displacement. When species concentrate in deeper zones, crowding can occur. Competition increases. Resources that were once spread across a greater vertical range become compressed. In some regions, deeper habitats risk being overburdened by the sudden influx. At the same time, fishing pressure in deeper waters is rising as surface stocks decline. Some species are chased into deeper zones only to encounter new threats. Others find refuge temporarily but risk long term decline if their new habitat cannot support them.

Whole freediving destinations are changing as a result. Islands that once offered rich shallow reefs now see barren coral fields and fish communities pushed beyond recreational depths. Spearfishers who once hunted at twenty meters now find the same species at thirty or thirty five. Warming waters in the Mediterranean have driven traditional reef fish into deeper refuges, while newcomers from warmer regions arrive to fill the vacated space near the surface. The identity of each ecosystem is shifting, often faster than local regulations or community knowledge can adapt.

For freedivers, this vertical displacement offers an unexpected window into climate science. Every descent becomes a survey. The temperature changes on your skin, the presence or absence of certain fish, the density of plankton in the midwater column, the flavor of the thermocline, and the visibility gradients all reveal how the ocean is reorganizing itself. Freediving becomes a way to witness climate change not as an abstraction but as a real, layered transformation unfolding in front of you.

There is a deeper philosophical dimension to this shift. Species are not just fleeing heat. They are fleeing instability. The surface is becoming a turbulent zone, subject to rapid and unpredictable changes caused by human activity. By moving deeper, species seek constancy. They seek a world where change still happens slowly enough that evolution, not crisis, can shape their responses. This is a reminder that the ocean’s stability is not uniform. It is defined by depth. The deeper layers act as memory, preserving the patterns of a world that once existed above.

Yet this refuge has limits. The deep ocean is not infinite. Its ecosystems are highly specialized and sensitive. A sudden influx of surface species can destabilize them. And while deeper waters are buffered from rapid warming, they are not immune. Heat is already penetrating greater depths than previously observed. The refuge that species seek today may not be available tomorrow. In some regions, the thermocline itself is shifting downward year by year. What is safe now may be inhospitable in a few decades.

Still, the movement toward depth speaks to the adaptability of life. It reveals the strategies organisms use when confronted with stress. Some move sideways. Some move upward. Some alter their diets or breeding patterns. And some descend along invisible gradients, following the narrow band of conditions that allow them to survive. This is not retreat but resilience, although it comes with a cost.

As climate change accelerates, these shifts will continue. Some species will adapt successfully. Others will not. But observing these movements gives us insight into what the future ocean might look like. A world where shallow reefs are less colorful but deeper ecosystems become hubs of biodiversity. A world where the thermocline becomes an increasingly important boundary for ecological survival. A world where the definition of a healthy habitat is rewritten by temperature curves and shifting currents.

Depth as refuge is not permanent, and it is not universal. But it is real. And understanding the story behind this movement allows us to understand the ocean’s response to one of the greatest pressures it has ever faced. Freediving offers a way to witness this story, to feel the gradients firsthand, and to appreciate the delicate choices marine life must make when survival depends on finding the right layer in an ocean that is warming from the top down.

This is not only a story about species escaping heat. It is a story about resilience and about the subtle power of vertical space in the ocean. It is about the ways life navigates change and about the fragile refuge that depth still provides. And it is a reminder that the ocean is not a single place but a continuum of worlds stacked one atop the other, each with its own climate, its own dangers, and its own hope for survival.